This is the second of three posts examining the effects of the proposed Petone to Grenada link road on the network and natural hazard resilience of the Wellington road network. This post covers Earthquake and Natural Hazard Resilience.

Part 1 looks at network resilience.

Part 3 takes a closer look at the challenges of the Hutt Valley in particular.

You can download the full report as a PDF [2MB] here: Resilience WGTN P2G_v1.4

Natural Hazard Resilience – Petone to Grenada

Jump to Takapu Valley Extension

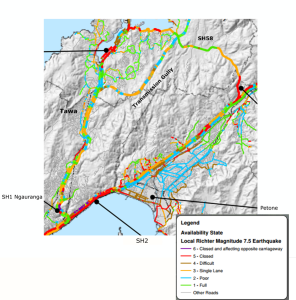

If there’s a big earthquake, both SH1 in the Gorge and SH2 along the harbour shore are expected to be closed. The map below shows “Availability State” – how bad will a given road be immediately after an event? For example, parts of SH1 through Tawa may be reduced to a single lane each way. Transmission Gully has a couple of short bits that may need a 4WD to get across.

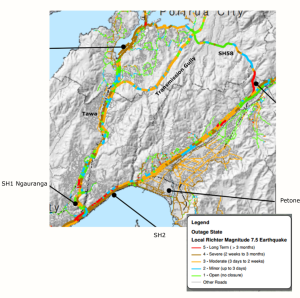

The map below shows “Outage State” – how long will a given stretch of road be in the state shown in the map above? They’ll be able to get most of SH1 usable, even through the Gorge – though maybe only via a few lanes – within a few days (though it appears they’ll need to divert to surface streets through Johnsonville). The northbound SH1 through Tawa will still be down to a single lane for two weeks to three months, though the southbound lanes should be back to normal much sooner. Transmission Gully likewise should be cleared in that 3 days to 2 weeks timeframe.

The Hutt, though, is expected to be cut off for weeks to months, depending on whether they can safely clear the slips along the shore there.

How will P2G perform in the event of a Magnitude 7.5 earthquake? What does it do for regional natural hazard resistance?

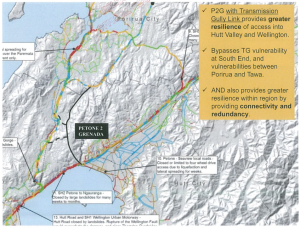

The slide NZTA presented to the local chief executives at their closed-door briefing back in November was this:

P2G “Resilience” slide from “Petone to Grenada and SH58: Presentation to EAG August 2014”, released under OIA

We don’t get Availability or Outage information for P2G – instead, it’s represented as a black road, apparently constructed of a magical “unbreakium” that won’t fail in an earthquake. Note that according to the sales pitch, Transmission Gully, which hasn’t even been built yet, is already a write-off and needs to be bypassed, as does the stretch of SH1 through Tawa, which as you can see from all that yellow and blue is likely to be the least damaged piece of highway in Wellington.

So how is P2G actually likely to fare in a major event?

On the Petone/Korokoro side it has 60-85 meter deep double sided cuts:

Cuts of that size – think canyon walls the height of the Intercontinental Hotel in Wellington, or the Quay Tower in Auckland – are capable of generating large landslips. The P2G Scoping Report 2014 notes in regard to the southern end of P2G that “failures in cut slopes can close the road for a few weeks”, and “high cut slopes reduce time for recovery.” Such slips can be very difficult to clear (think the Manawatu gorge), especially when working at the bottom of a canyon where aftershocks threaten to send more material down onto the diggers below. This means that the slips could not be quickly cleared, and the road might well be closed for at least weeks, and possibly even months.

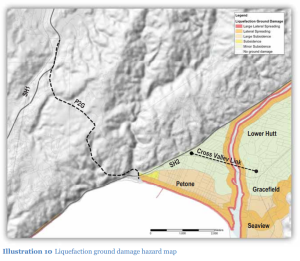

Then there is the fact that the road terminates in Petone, one of the most geologically/geotechnically problematic spots in the Wellington region, subject to subsidence, liquefaction and lateral spreading:

In addition, the area is subject to Seiches – a type of harbour tsunami that sloshes back in forth in a periodic oscillation, hammering Petone and the P2G terminus again and again.

Petone Tsunami risk map from WREMO – the P2G terminus would be in the orange high-risk area at the far left

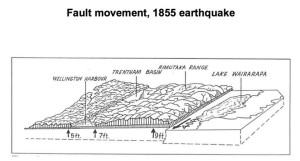

But it is potentially even worse than that. In the 1855 Wairarapa Earthquake Petone was uplifted about 2 meters.

The Wellington and Wairarapa faults tend to induce movements in opposite directions, so if the next major regional EQ is along the Wellington fault, then all of Petone could be thrust back down ~2 meters over the course of 60 seconds. The end result would be that P2G, even if it was made of unbreakium (and note the P2G/SH2 interchange at Petone is mere meters from the Wellington Fault), could end up linking to little more than a rubble-strewn lake.

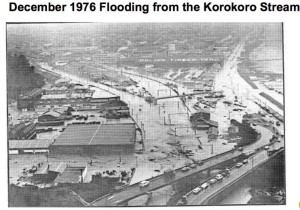

… And speaking of lakes, here’s the 1976 Korokoro Flood, caused by a large storm – that flooding is from Korokoro Stream, by the way, not the Hutt River. The photo below is of Ullrich Aluminium and the current Petone overbridge, right where P2G will connect to SH2 in Petone.

Petone is not the best place to put one end of a road intended to be a natural hazard resilience route, even if that road itself were not so vulnerable.

Natural Hazard Resilience – Takapu Valley

We’ve already addressed how the Takapu link does not offer very much in terms of network resilience, how about natural hazard resilience? The resilience specialist consulted for the P2G Scoping Report rated the Takapu Alignment highly.

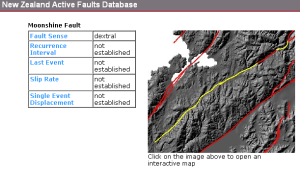

Unfortunately, the specialist made another mistake and also missed the fact that the proposed alignment runs directly along and atop an active uncharacterized fault:

GNS has listed the Takapu Fault as a spur of the Moonshine Fault. The Moonshine Fault has a nice long failure interval – NZTA sources quote a figure of 11,000 years. Unfortunately, geotechnical sources we’ve consulted tell us that it’s not correct to assume that the Takapu spur operates at the same displacement or interval that the Moonshine Fault does. That’s why GNS has all those “not established”s in the database.

The fault itself is not necessarily the problem – you can’t throw a stone in Wellington without throwing it across a fault line, after all. The problem is that Takapu Valley is narrow and in places quite steep, and the best land has long been occupied by power pylons. Lots of them.

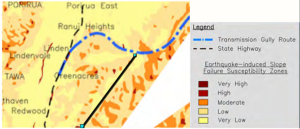

Even with the best alignment they could pick, the Takapu link road features “moderate height cuts that may fail, closing the route for up to two weeks”. (The section of SH1 it is supposed to “bypass”, by contrast, is expected to remain usable immediately after a quake.) The proposed narrow, two-lane Takapu extension runs through terrain with a moderate to high risk of slope failures, particularly at the southern end, which has an overall greater extent of at-risk slope than the Duck Creek and Linden sections of Transmission Gully. (The worst bit is the southern end of the valley, unfortunately cut off in the image available.)

Images from Appendix A, Statement of evidence of Pathmanathan Brabhaharan (Brabha) (Geology and geotechnical engineering) for the NZ Transport Agency and Porirua City Council. 18 November 2011

This is the other shoe dropped by the fault line: even if you give the fault itself minimal clearance (and first they’d need to pay GNS to figure out where it actually is, because that bit you can see – where you can see it at all – is only where it happened to break the surface the last time it ruptured), the rock all through there has been fractured and crushed by the movement of the fault over millions of years.

When describing the resilience aspects of the southern end of P2G, the specialist repeats multiple times: “Away from poor rock conditions and faults [the cuttings] can be engineered to reduce failures in earthquakes”, “Likely to have better rock conditions being further away from the Wellington Fault Zone”, “Rock conditions are likely to be better being away from the Wellington Fault zone, and a short crossing of the inactive Korokoro Fault scarp.” If the fault isn’t the problem, the rotten rock near the fault is. It’s difficult to build on – as the Transmission Gully team has discovered attempting to site the foundations for the Cannons Creek viaduct, which nips off the top of the valley – and it’s far more likely to fail than even the usual Wellington “wheatbix” greywacke.

In a series of answers to questions raised by Hutt City Councillors, the P2G project team identified as key risks for Option D specifically:

- Geotechnical, relating to the stability of the large cuts and differential settlement within road embankment fills required to form a link road in complex terrain

- Geometric constraints, particularly with respect to horizontal curvature and gradient, as a result of difficult terrain

An alignment which gives a safe clearance to the fault line may not be possible, with the pylons to the west and the steep hill faces to the east – there’s also the Wellington water main and the gas main to avoid, particularly at the north end of the valley. They could be forced into an alignment requiring still higher, more vulnerable cuts into multiply-fractured, slip-prone hillslopes – though if they go too high, they’re into more power lines.

Speaking of which:

The Wellington Region Road Network Earthquake Resilience Study released by Opus in August 2012 pays special attention to sections of the network – particularly in Upper Hutt – that are at risk from fallen power lines.

The alignment of the proposed Takapu extension weaves under and through the 33, 66, 110 kV lines and under the 220 kV lines and the HVDC link – right up through the spot where more than a dozen sets converge on the Takapu Substation. Even when well-sited, the pylons themselves may fail in an earthquake or severe weather event. One of the sets of pylons running alongside the proposed road alignment was built in 1924.

Conclusion

P2G does not provide very good regional natural hazard resilience, due to the vulnerabilities of the deep cuts on the Petone end, and the simple fact that it connects to Petone, one of the most geotechnically problematic areas in the region.

The Takapu Valley has mediocre to poor natural hazard resilience, due to its constrained alignment along an active fault line in steep, fault-fractured terrain. What it does do is add extra lane-kilometres of road that will need to be cleared (or abandoned) after a disaster – likely to be low priority compared to the adjacent Wellington RoNS corridor.

Part 3 looks at road access to the Hutt Valley after a major event.

Part 1 looked at network resilience, in the case of a crash or congestion.

You can download the full report as a PDF [2MB] here: Resilience WGTN P2G_v1.4